The problem

When I joined the ScreenSense(erstwhile "Workflow Engine") team, we had a data problem. Not a "we have too much data" problem. The opposite.

Each time the team or I needed to validate a hypothesis or quantify an issue, we hit the same wall: the data either didn't exist or wasn't surfaced in any usable form. We had raw logs buried in our data warehouse, but no database access & raw, unformatted data meant I was heavily reliant on Engineering teams & hours of manual post processing to generate insights.

This made prioritization feel like guesswork. Leadership was relaying individual customer NPS feedback and escalation reports to seek input & figure out why. When a customer complained loudly, we'd scramble. But I had no way of knowing if that complaint represented 1% of our users or 50%.

The cost

Every investigation into failure rates, self-service quality, attempt to size a problem, effort to justify a priority required starting from scratch. I'd work with engineering to pull logs. Cross-reference account IDs. Build one-off queries. Aggregate results in spreadsheets. Then do it all again the next week when someone asked a slightly different question.

3-5 days

Time to insight

Minimum time to answer any data question, from raw pull to presentable insight

The opportunity cost was brutal. Every day spent on manual analysis was a day not spent actually solving the problems we were investigating.

What changed?

I took ownership of fixing this. The approach had two parts.

- Plotted "what do we have?" vs "what do we need?" to answer questions about customer behavior and product usage

- Worked with engineering to define what we needed to start tracking & isolated data points that needed a code push

- Once data was pushed, worked with our data team to surface this data in a presentable, recurring format. Dashboards that updated automatically. Looker tables that let me slice the data different ways. No more one-off spreadsheets.

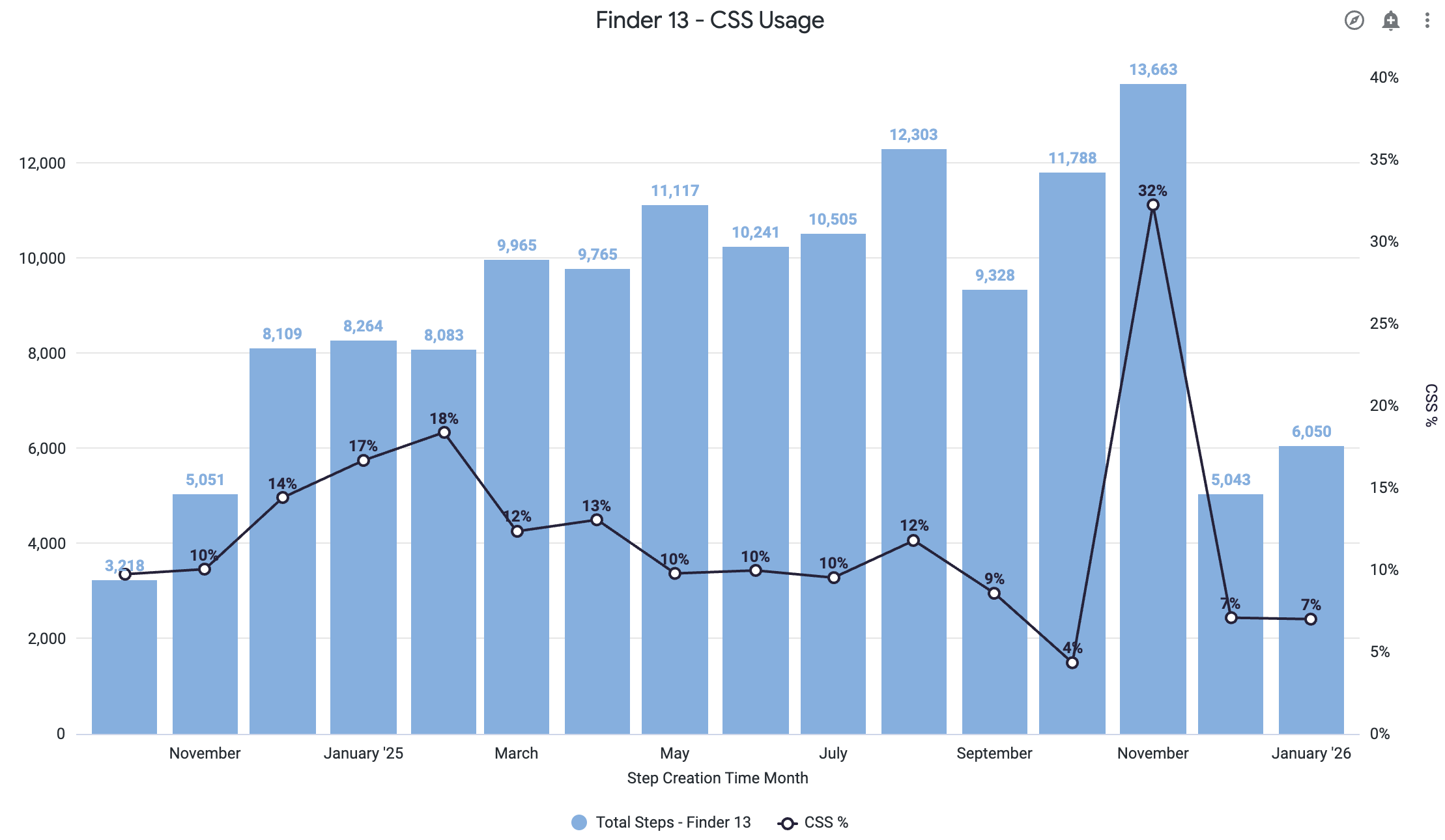

- CSS selector usage tracking: How often does our algorithm need to be supplemented by manual CSS selector addition by an author?

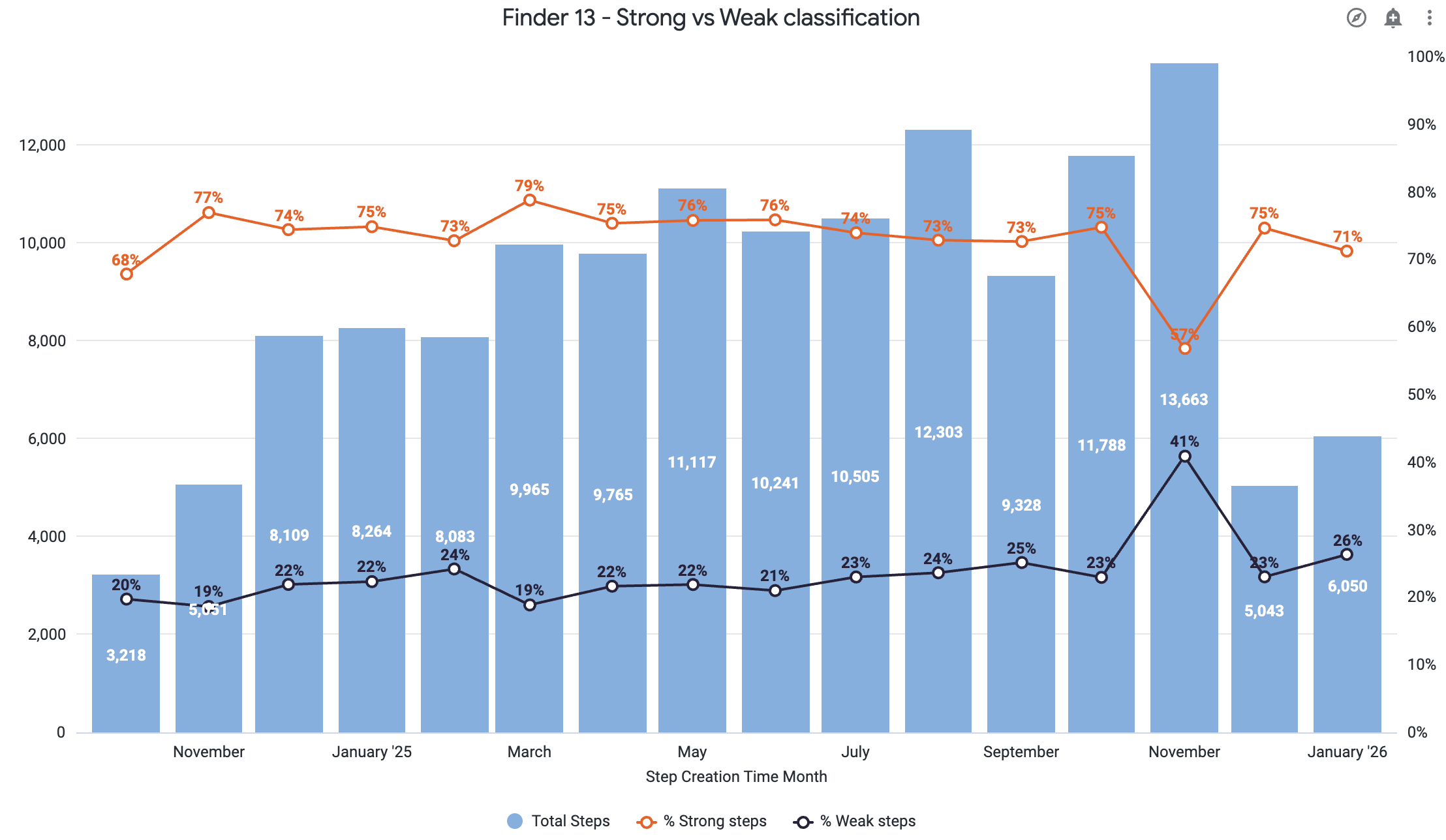

- Element strength scoring: Quantifying the reliability of our element identification algorithm, directly assessing if manual intervention via CSS selectors is needed

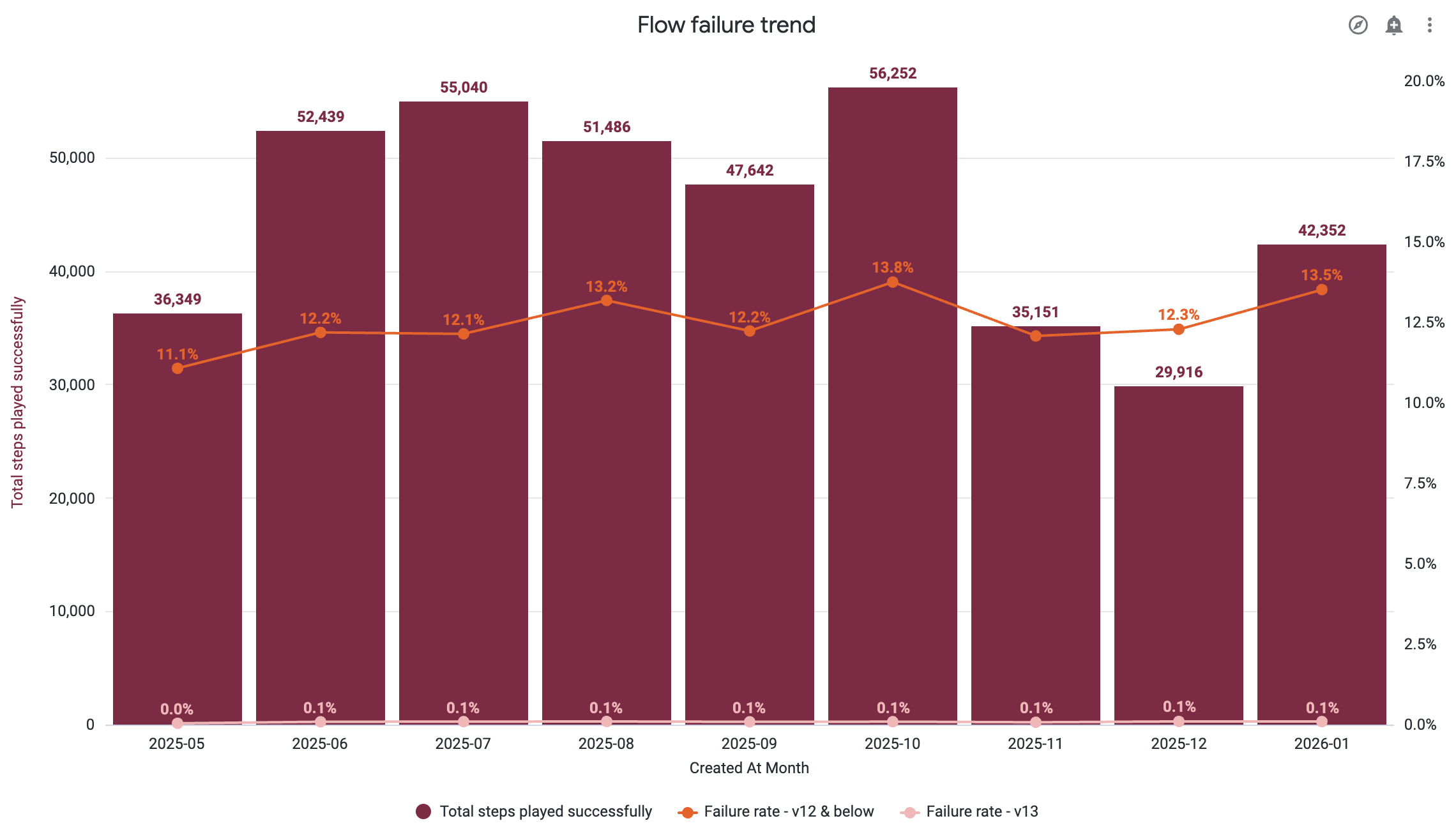

- Flow failure monitoring: End-to-end tracking of content failures at runtime

- Customer-level aggregation: Understanding failure patterns across different implementations

The key was building dashboards that updated automatically, replacing our spreadsheet approach with always-current visibility.

Note: This wasn't a "pause everything and build instrumentation" initiative. My reasoning was simple: You can't fix what you don't track. Nor could we make good prioritization decisions without reliable data.

The result

Hours

Time to insight

Down from 3-5 days. Engineering effort shifted from ad-hoc data pulls to instrumenting during development.

We could finally see, in real time, where to focus. Patterns emerged that we'd never reported or considered before. Conversely, some "critical" escalations turned out to be true outliers.

The philosophy

The goal is to be data-informed, not solely data-driven

This experience crystallized a principle that guides how I work: be data-informed, not data-driven.

Instrumentation doesn't make decisions for you. It tells you where to look. It quantifies trade-offs. It can reveal what you don't know. You need the discipline to act on what the data reveals, even when it contradicts your assumptions. But the judgment, the "what to do about it," is basically the job and what a Product Manager is hired for.