Context

Whatfix's core platform - it's element detection(Finder) algorithm was constantly evolving to solve two key problems for our customers - a self-served, "point-shoot-create" experience on the authoring side that ensures reliable element latching & accurate content playback during runtime.

The problem? The authoring side was not a simple "point-shoot-create". Web applications are built in a variety of ways with each organization choosing their own best practices. Whatfix is an overlay, which means our algorithms depend on the HTML DOM structure. Infact, the quality of the Finder algorithm is directly proportional to how well defined an application's HTML elements & their attributes are.

This manifested into roughly 18% of all "elements captured" having to rely on manually configured CSS selectors. Our core target audience - non technical content authors/instructional designers were losing confidence in the promised "point-shoot-create" platform. This fragility also impacted runtime reliability, with content failure rates hovering between 15-20%.

15-20%

Content failure rate

Before algorithmic improvements

As an outsider, it would be tempting to throw AI at the problem. Element detection sounds like a computer vision problem, right? Infact, we did attempt computer vision but in 2022-2023, the performance & accuracy that we were looking for just didn't exist.

It is also worth noting that at this time, LLMs did not exist. But we believed the fundamentals could be improved without heavy investment in machine learning.

Finder 11: Understanding the baseline

The algorithm already used a patented, proprietary anchoring and pillar logic for element detection. It worked for the vast majority, but it was brittle & very susceptible to changes in DOM structure.

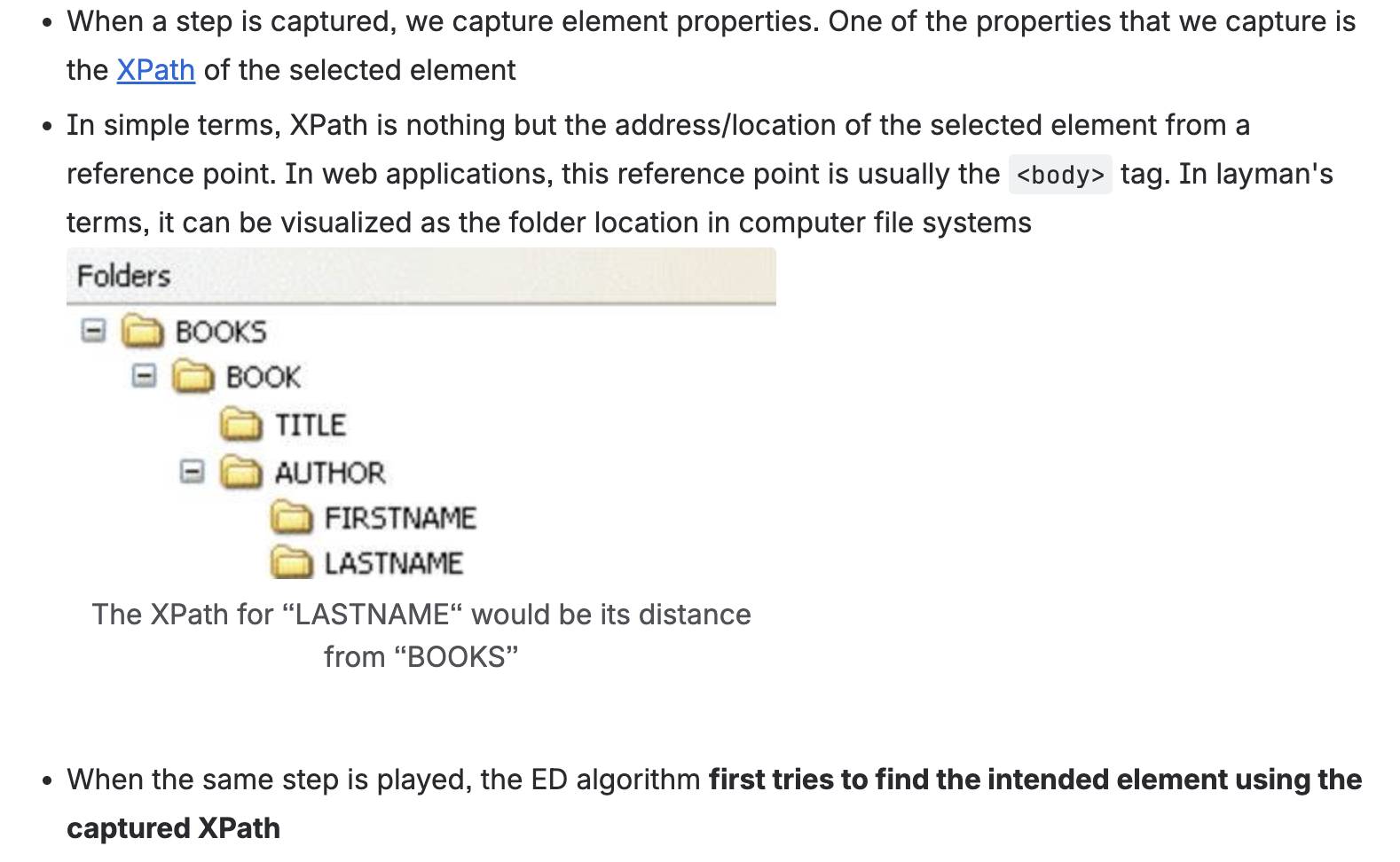

We investigated & the key finding was the algorithm's treatment of the XPath filter. Think of XPath like a file path on your computer. Just as you navigate to a file through folders (Documents → Work → Reports → Q1.pdf), XPath helps navigates to the target element through the DOM tree.

The problem: Our XPath capture was too rigid. We captured every node in the path, including dynamic ones that changed frequently. When any node in that path changed, the whole element finding operation broke.

Before attempting to improve, we invested in instrumentation. You can't optimize what you can't measure. See Case Study Zero for more.

Finder 12: Fixing the rigidity

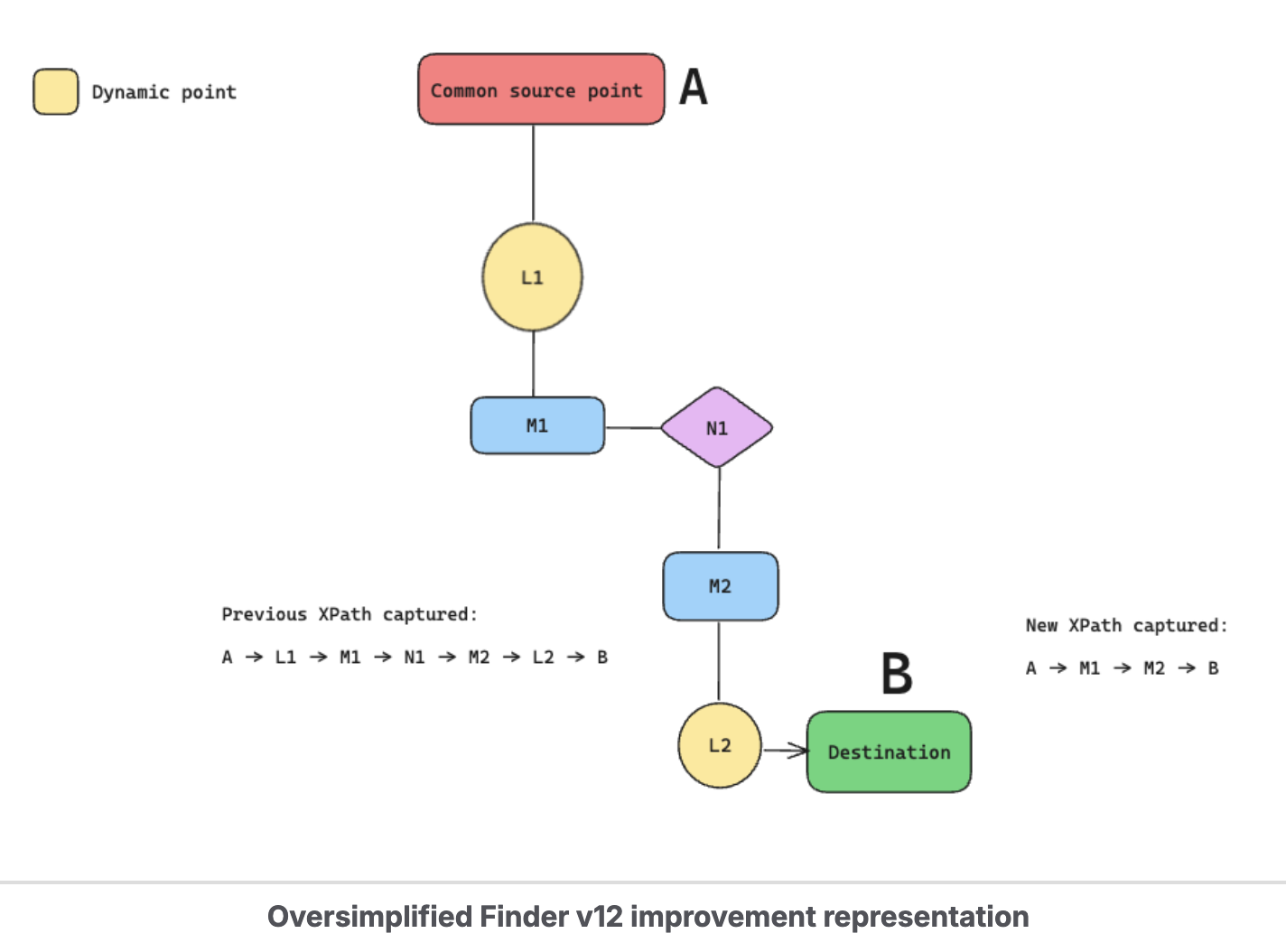

The first major iteration focused on a simple insight: our XPath capture was too rigid & was capturing more than what was needed.

What does this mean? Well, imagine navigating to a destination through a series of landmarks. The old approach captured every landmark along the way, including temporary ones like a parked food truck. When the food truck moved, your directions broke.

The fix: Skip the volatile landmarks. Only capture stable reference points.

The result

12-15%

Content failure rate

Down from 18-20%

11-12%

CSS selector dependency

Down from 18%

Finder 12 delivered meaningful improvements, though not yet the 10x we were aiming for.

Finder 13: The breakthrough

This is where things came together. Version 13 combined two capabilities that unlocked the under 2% failure rate we were chasing:

Element strength tracking: We began tracking "strong" & "weak" elements, identified during authoring. Weak elements - typically meant multiple matches, or a potentially wrong element. Strong elements - algorithm confidently returned exactly one correct match

This instrumentation gave us visibility into where the algorithm was struggling. For the first time, we could quantify the problem rather than react to individual failures. And critically, it laid the foundation for targeted AI intervention later.

Algorithm-driven system-generated selectors: The algorithm now automatically generated CSS selectors for elements where the default algorithm wasn't performant enough. This meant "refining" a potentially weak element to a strong element. Pure algorithmic automation, no human or AI involved.

The results

Under 2%

Content failure rate

Down from 12-15%

7-10%

CSS selector dependency

Down from 11-12%

This was the 10x improvement we'd been working toward. Achieved entirely through algorithmic discipline.

Business impact

$500K-1M

Influenced ARR

Platform differentiation in deals won

What I learned

Knowing when NOT to use AI is as valuable as knowing how to use it.

We achieved 10x improvement in reliability without any machine learning. The algorithms weren't sexy, but they worked. More importantly, they gave us a solid foundation. When we eventually did add AI, it was strategic.